Both Schaeffer and Sayers address their contemporaries on the same topic: an ugly side of Christianity. Both share the same background: preacher's kids. Thus, as children of Christian ministers, these two rhetors (i.e., speakers and writers) criticize and critique Christianity from the inside: as insiders.

For me, this is very interesting stuff. What Schaeffer and Sayers have to say, the personal angst and authority with which they say it, and exactly how they say it is particularly interesting to me for the following reason: I share this same background with these two. My father is also a Christian minister (a pastor, a preacher, a missionary). Thus, I greatly appreciate the logos, the ethos, and the pathos of the son of Francis A. Schaeffer and of the daughter of Henry Sayers.

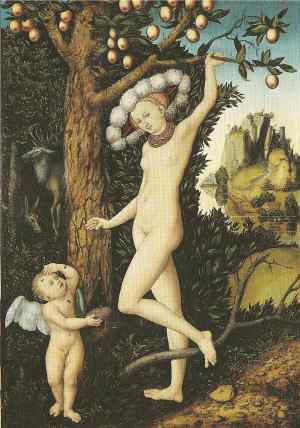

I would, nonetheless, like us all to notice a difference between these two preacher's kids grown up: one "had to" live her life in her body, in the Christian church, sexed female. ("Fe-male" is our marked English word, and how marked it has been in the English-speaking Christian church.)

Therefore perhaps, this same one, Dorothy Sayers, has been called the author of the "first feminist mystery novel": Gaudy Night. But if you read some of those Uncommon Opinions of hers, then you know how she understood how many people would mean the word feminism. And if you have read her book, Are Women Human?, then you know how "irritated" the label, "feminist," made Sayers. She insisted "that a woman is just as much an ordinary human being as a man, with the same individual preferences, and with just as much right to the tastes and preferences of an individual" (page 24). She actually didn't like labels, didn't like being put into a box by labels. And she didn't like women being put into boxes, especially not by religion, Jewish or Christian. So she wrote to complain about the opinion of men, of Judaism and of the Church:

Women are not human. They lie when they say they have human needs: warm and decent clothing; comfort in the bus; interests directed immediately to God and His universe, not intermediately through any child of man. They are far above man to inspire him, far beneath him to corrupt him; they have feminine minds and feminine natures, but their mind is not one with their nature like the minds of men; they have no human mind and no human nature. "Blessed be God," says the Jew [a man of course], "that hath not made me a woman."

God, of course, may have His own opinion, but the Church [of Christian men of course] is reluctant to endorse it. I think I have never heard a sermon preached on the story of Martha and Mary that did not attempt, somehow, to explain away its text. Mary's, of course, was the better part--the Lord said so, and we must not precisely contradict Him. But we will be careful not to despise Martha. No doubt, He approved of her too. We could not get on without her, and indeed (have paid lip-service to God's opinion) we must admit that we greatly prefer her. For Martha was doing a really feminine job, whereas Mary was just behaving like any other disciple, male or female; and that is a hard pill to swallow.

Perhaps it is no wonder that the women were first at the Cradle and last at the Cross. They had never known a man like this Man -- there never has been such another. A prophet and teacher who never nagged at them, never flattered or coaxed or patronised; who never made arch jokes about them, never treated them as either "The women, God help us!" or "The ladies, God bless them!": who rebuked without querulousness and praised without condescension; who took their questions and arguments seriously; who never mapped out their sphere for them, never urged them to be feminine or jeered at them for being female; who had no axe to grind and no uneasy male dignity to defend; who took them as he found them and was completely unselfconscious. There is no act, no sermon, no parable in the whole Gospel that borrows its pungency from female perversity; nobody could possibly guess from the words and deeds of Jesus that there was anything "funny" about woman's nature.

But we might easily deduce it from His contemporaries, and from His prophets before Him, and from His Church to this day [of course mainly men]. Women are not human: nobody shall persuade that they are human; let them say what they like, we will not believe it, though One rose from the dead.

(pages 66-69, Are Women Human)But this long quotation from Sayers is here in the post only because most of us readers know her best for her translation of Dante's incredible poetry. It's one of the best translations ever, and Sayers's rendering of his verse may be why many of us know Dante. Alinza Dale Stone, writing Maker and Craftsman, a wonderful biography of Sayers, notes that "She also was sure that when Hell did come out she would be attacked for treating Dante as a great storyteller instead of a superhuman 'sourpuss'" (page 141). If you know Sayers's story among men, then you get that certainty of the attack, which did come against her. So when Sayers critiques the church of her father(s), it goes something more like this (from "The Other Six Deadly Sins" in the concluding pages, 82-85, of Creed or Chaos):

But the head and origin of all sin is the basic sin of Superbia or Pride. In one way there is so much to say about Pride that one might speak of it for a week and not have done. Yet in another way, all there is to be said about it can be said in a single sentence. It is the sin of trying to be as God....

The Greeks feared above all things the state of mind they called hubris--the inflated spirits that come with overmuch success. Overweening in men called forth, they thought, the envy of the gods. Their theology may seem to us a little unworthy, but with the phenomenon itself and its effects they were only too well acquainted. Christianity, with a more rational theology, traces hubris back to the root-sin Pride, which places man instead of God at the centre of gravity and so throws the whole structure of things into the ruin called Judgment....

Human happiness is a by-product, thrown off in man's service of God. And incidentally, let us be very careful how we preach that "Christianity is necessary for the building of a free and prosperous post-war world." The proposition is strictly true, but to put it that way may be misleading, for it sounds as though we proposed to make God an instrument in the service of man. But God is nobody's instrument....

"Cursed be he that trusteth in man," says Reinhold Niebuhr "even if he be pious man or, perhaps, particularly if he be pious man." For the besetting temptation of the pious man is to become the proud man: "He spake this parable unto certain which trusted in themselves that they were righteous."

My Lord Bishop--Ladies and Gentlemen--it has been my privilege to suggest to you that in your work for the Moral Welfare of this nation you will be doing a great thing if you can persuade the people that the Church is actively and anxiously concerned not with one kind of sin alone, but with seven sins, all of which are deadly, and not least with those which Caesar sanctions and of which the world approves....